Week 5 Lab: Turtle Graphics

Git Repository: https://gitlab.msu.edu/mi-250/turtles

For this lab, we are going to use a Git repository like we did for last week. The first thing you should do is fork the turtles repository (link above), add your partner, Caitlin (geierac) and Shiyu (xiangsh2) to the repository, and then clone the repository onto your computer. Refer to the Git reference if you’ve forgotten how to do this. Remember: only one person in your pair needs to fork the repository.

For this lab, we will be working with Turtle Graphics all day. There are a LOT of commands you can use for Turtle, and you don’t have to memorize them all. Instead, you can refer to the documentation:

I’d recommend that the navigator (the person who isn’t driving) keep the documentation open to refer to while you work.

I also strongly advise you to write your code in small chunks and test it frequently. Add one or two lines of code, and then run it to see what happens. If it’s not working, tinker with it until it does. Then add one or two more lines, run it again. And so on. The more often you run it, the more you’ll understand what it is doing and the easier it will be to troubleshoot when things go wrong.

Draw some things

When I refer to “the turtle” in these exercises, I mean the arrow in the Turtle drawing window. Think of it as a small turtle that crawls around on the screen, leaving a trail behind it.

Exercise 1: Finish the square

In the Git repository, you should see a program called square.py. This program is supposed to draw a square on the screen that looks like this:

However, the program isn’t finished! Run the program with python square.py (or python3 square.py on Mac) and see what happens.

Edit the program to finish drawing the square. Remember that the right() and left() commands turn the turtle in degrees – 360 degrees turns the turtle all the way around so it is facing the same way it started. 90 degrees is a quarter of the way around (a right angle). 180 degrees turns the turtle around to face the opposite direction.

Exercise 2: Finish the stick figure

In the Git repository you should see a program called person.py. This program begins to draw a stick figure using Turtle. Run the program to see what it does.

It should start to draw a stick figure, and then wait for you to close the window. Python will keep running the program (even if it’s not doing anything) until you close the Turtle drawing window.

Write the code to finish drawing the stick figure. The person.py file contains some comments (text with # in front of it) for what code you’ll need to write to finish it.

Don’t try to do this all at once. Start by drawing on a piece of paper without lifting up your pen: what do you need to do with the pen? (You can use the whiteboard in the classroom for this too, if you want.) Next, write one or two commands, and then run the program to see what happens. Write more commands, and see what happens.

Once it is finished the person should look something like this:

Note: Pay attention to the direction the arrow is facing. After drawing the code that I wrote, it is facing down. That means if you turn right, it will end up facing left (because if you facing down and turn right, that’s where you end up).

Exercise 3: Pen Up and Down

Next, we are going to do a bit of writing with our turtle. Create a new program, called MI.py, that writes the two capital letters “MI” next to each other. The two letters should not be touching each other. It should probably look something like this:

To get the gap between the “M” and the “I”, you can use the penup() and pendown() functions to lift up the pen after drawing the “M” and put it back down before starting the “I”.

Before you can use any of the Turtle commands, you need to remember to import the Turtle library. Importing brings in additional functionality into python that it normally doesn’t have. The Turtle library doesn’t come preloaded into Python, so we have to import it to be able to use it. To import the Turtle library, put this line at the top of your program:

from turtle import *

Note both of the previous programs did that, too.

Also, for Turtle programs, it helps to end the program with done() - put it in the last line of the program. This causes the program to keep the Turtle window open after it’s done drawing so you can see what the drawing looks like.

Don’t forget to save this file into the Git repo on your computer, so you can then add, commit, and push it to your Git repository on GitLab. If you haven’t switched drivers already, now might be a good time to do that.

Exercise 4: Names, squared

For the next exercise, create a new program called name.py. This program should use the write() function to print out a name. Decide whether to use your name or your partner’s name. It should also draw a red box around the name.

Here is mine:

Note: you can change the color of the pen with pencolor("red").

You can also change the font and size if you want to. If you want to try this, look through the Turtle documentation (linked at the top of this lab) to figure out how to do it. (Hint: you can add more things inside the write() function!)

Hint: Remember to add from turtle import * to the beginning of your name.py program and done() to the end.

Interactive Drawing!

The program guestbook.py is a simple guest book app that prints out a name on the screen using Turtle. If you run it, it should print my name and move the turtle a bit.

Exercise 5: Input name from user

Turtle has a function called textinput() that allows you to ask the user for a text input, which you can then save to a variable and use elsewhere. Modify the guestbook program to ask the user for their name, and then use Turtle to write the user’s name on the screen underneath my name.

textinput() works similarly to input(), which we’ve used in the past. But there are two main differences:

- Unlike

input(), which prompts the user in the terminal,textinput()causes a window to pop up asking the user for information - Also unlike

input(),textinput()needs two pieces of information: the title of the window (text that shows up at the top of the input window), and the prompt that is displayed to the user.

For example, the code:

name2 = textinput("Name", "Please enter your name")

would pop up a window titled “Name” and ask the user to “Please enter your name”. Whatever the user enters in the window would be saved into the name2 variable.

Exercise 6: Third Name

The guestbook should have two names in it now - my name, and then a name captured via textinput() underneath it. Now modify the guest book to ask the user for a third name, and display the third name below the second one. You’ll have to move the pen down again before writing the third name to make sure the names aren’t on top of each other.

Hint: You’ll likely want to have three different variables at this point, each storing a different name.

Exercise 7: Looped Guestbook

Now you should have three names in your guestbook, with the turtle moving between each name. You might have noticed that you had to repeat the move code and the input code to get it to work.

When you see repeated code, that can be a good time to use a loop instead. Put the code that asks for a name, draws it, and then moves the turtle down into a loop so it will keep asking for names and then printing them out, one after the other.

Hint: a while loop will probably work better than a for loop for this. Go back to the Guessing Game exercises in the Counting and Loops lab if you need a reminder on how to use while loops. Note you can end the program anytime by closing the Turtle window, so you don’t need to worry if the loop is infinite.

Exercise 8: Quit the Guestbook

Add an option for the user to quit the guestbook program if they type the word “quit”. You can do this by putting an if statement inside your loop:

if userInputVariable == "quit":

break

The break keyword does what it says on the tin - if the if statement is true, it will break the loop.

Test it to make sure it works! You may have to try putting the if statement in different places inside the loop to make sure it runs when it’s supposed to.

Seeing Stars

Exercise 9: Star

Create a new program called stars.py. For this program, write a program that draws a 5 pointed star. Here’s the catch: you must use a for loop to draw the star. If you do it right, the star can be drawn using only 3 lines of code.

Note: The angle at a point of a star is 144 degrees.

Note 2: Drawing a star should just involve moving forward, turning 144 degrees, moving forward, turning again, and so on until the star is finished.

One finished, it should look like this:

Hint: Remember to add from turtle import * to the beginning of your stars.py program and done() to the end.

Exercise 10: Row of stars

Next, modify your program to use a for loop to create a row of 5 stars next to each other. You should use the same code you wrote above to draw a single star, but put it inside a loop with some additional code between the stars so that the turtle moves to the right to get ready to draw the next star.

Hint: It is possible to have a for loop inside of another for loop - this is called having a nested loop.

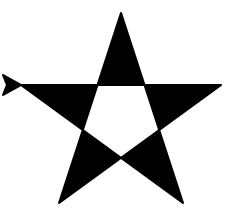

Exercise 11: Fill In the Stars

Modify your program to fill in the stars with a color. You can specify the fill color using the color() command. Use begin_fill() when you start drawing to begin filling in the stars, and end_fill() after the star has been drawn. For this exercise, fill the stars so they’re all black (color("black")).

Note: The center of the star will not be filled in with color - that’s expected! It’s to do with the way Turtle calculates what parts of the shape should and shouldn’t be filled.

Hint: When you want to fill a shape with color, the order of things really matters. The color needs to be set before you start drawing the shape. You should also use begin_fill() before the code that draws the shape, and end_fill() after the shape has been completely drawn. In the case of the star, the loop which draws a line and then rotates the turtle 5 times in a row is what draws and individual star, so begin_fill() and end_fill() should be wrapped around that loop.

Exercise 12: Brightly Colored Stars

Black is boring. Make the stars brightly colored. Here’s a handy resource for colors you can use in Turtle.

If you want an even broader range of colors, you can also use HTML color codes, also known as hex codes. Here’s a good color picker. Google can help you figure out how to use hex codes with Turtle.

Play around and find a color you and your partner both like, and make all the stars that color.

Bonus: can you make the stars multiple colors?

Exercise 13: Lots of Stars

Now that you have the commands to draw a star, let’s draw lots of stars. Using nexts for loops, modify your previous program to draw 50 stars in a 10 by 5 grid.

Hint: putting the command speed(0) near the top of your program will speed up the Turtle drawing so you don’t have to wait as long.

Hint 2: You’ll need to move the turtle in between each row of stars so it starts in the right place to draw the next row.

Challenges

If you finish all of the exercises before the end of class, try at least one of the challenges below.

Challenge 1: Draw more shapes

You’ve drawn a square and a star so far. Use Turtle to draw these shapes as well:

- Pentagon (5 sides)

- Hexagon (6 sides)

- Octagon (8 sides)

If you aren’t sure of the angles you need to turn the turtle in order to draw these shapes, use Google to look it up!

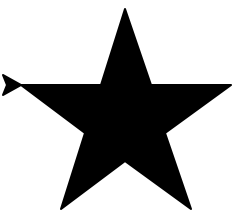

Challenge 2: Completely filled star

Draw the star differently so that the entire inside part of the star is filled, like this:

Hint: You can do this by drawing the outline of the star rather than drawing criss-crossing lines. What angles would you use for that?

Challenge 3: Stars on the U.S. Flag

Modify the program to create a blue background, and change the stars to be solid white. You can set the background color using bgcolor(), or by drawing a large square and filling it in with the color you want before you draw the stars.

Bonus: draw the 50 stars in the pattern they appear on the US Flag.

Challenge 4: Random Number of Stars

Instead of drawing a set number of stars in a set number of rows, draw a grid of stars with random dimensions using the random library. You’ll probably want to provide boundaries to the range of random numbers that are generated so you don’t accidentally draw a million rows (that would take forever!).

Bonus: also make each star be a random size.

Hint: If you need a refresher on the random library, look at the first few exercises in Lab 4. Also remember to add import random at the top of your program.